|

JOGA BONITO FROM STREET TO STADIUM | |

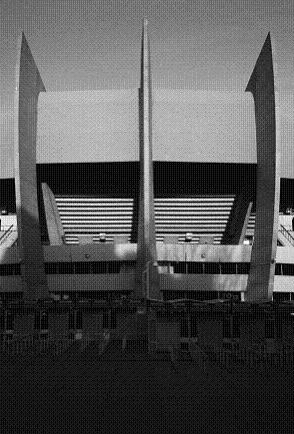

HOLY GROUNDS Photography by Cyprien Gallaird Text by Payam Sharif In Tehran, I play indoor football, in small arenas to the west of the city, past the airport, where the landscape turns arid and beige before returning gloriously to green near the Karaj Dam. In London, I play 5-a-side outdoor football with Bangladeshis and Somalians in smaller, more combative fields that pop up amid the public housing estates in East London like wild growths. In Houston, with Central Americans in the never-ending, saturated green fields of Bear Creek Park, off Interstate 10, the highway that cuts across America, connecting Florida to California. In New York, with Europeans in Riverside Park on the West Side, along the Hudson River. In St. Petersburg, with Georgians and Central Asians near the Smolny Institute where Lenin planned the Russian Revolution of 1917. In Paris, well, I skip the city and head to its outskirts. More precisely to the suburbs around Paris' periphery, with views onto Villetaneuse, I meet up with some of the legendary old-school rap crews from the 1990s for a quick game. I am not attempting to pass football off as some sort of ersatz Esperanto or, worse still, a vehicle for cultural tourism. But it is, irrefutably, one of the remaining lingua francas shared by an increasingly splintered global society. Today, reality television runs rampant on our channels. The elegant black and white of yesterday's dailies has been replaced by the half-hearted color of today's broadsheets. There is no longer any music on music television. Despite all this, we try desperately to find a common denominator that does not dumb down or underestimate its audience, ourselves. Alas, football is one of the few things that manages to do so. Football does not gloss over difference, nor does it emphasize it. Like those science textbook drawings of a bone in cross-section, with nerve-endings, blood vessels, and muscle wrapped tightly together, the sport is a burrow that cuts through and across national, socioeconomic, cultural, and even architectural divides. How else does one explain the default elegance of a football field, regardless of its context, the weather, or the people playing on it? It matters little if the accessories are military aircraft, a stack of hay, or a barbed-wire fence. It is almost as if the field itself were resistant to ornament, as if it had taken its cue from a certain celebrated Austrian architect and went so far as to persecute ornament as a crime. For no matter how sophisticated the actual construction enclosing it-whether it's Parc des Princes or La Noue housing project in Bagnolet-the football field remains steadfast, intransigent, almost stoic. In Brasil, the horizontal typologies of the favelas suggest linear narratives, where a corner tells of a glorious pass or the dent in the side of a home reveals an unbelievable shot. The housing estates surrounding Paris, however, offer an entirely different typology, a vertical one, one of control and power. Yet even here, the football field adds an element of mute elegance. Around the factory at Meaux, for example, it heightens the effect of the buildings' strangely Scandinavian minimalism. Elsewhere, the field gives the apartment towers a certain redeeming majestic stature; they seem to stand in for seats at a stadium where residents, like royal guests at some jousting match, can watch as if they were the only spectators, as if the game existed for their eyes only. The tower blocks surrounding the field give a new meaning to the term "pay-per-view." All the images in Holy Grounds have been taken within a 25 km radius of Paris, a city whose master plan and consistently stunning architecture leave some people frustrated, even exhausted, with its overwhelming homogeneity. The suburbs surrounding Paris are often dismissed for their underwhelming architecture, whereas they are, in fact, devastatingly diverse. If the faux geodesic domes at Meaux, the prison at Bois d'Arcy, or the American base at Aulnay-sous-Bois are the appendices to a book in which Paris is the main plot, then perhaps we should turn immediately to the end of the text and read backwards. The housing projects in the Paris metropolitan area were built out of an unbridled optimism, out of an idea that came from above but seemed to crash when it landed on its feet. These football fields, however, convey an entirely different trajectory: ungroomed, unaligned, they manage to show up the na�vet� of the site's master-plan. Any residual utopianism here has been soaked in grass-roots spirit, starting very much at the bottom and making its way upward. Like many a European, Cyprien Gaillard is fascinated by the uncanny character of American suburbs: the uniformization, the lack of social activity, the veneer of propriety. In this series, he has turned towards his native city, Paris, and the banlieux that sit defiantly on its edge. His photos champion not what the game of football has become-not the glamour, the pomp, the spectacle-but rather what it used to be at its origin and continues to be on innumerable fields all across the world: the rare place where future greats, fathers, cousins, class-mates, colleagues, and neighbors, all like stars, come to collide.       torna indietro |

Newsletter

|

|

Main Partners

| COPYRIGHT FUORISALONE / STUDIOLABO 2006 | PROGETTO DI STUDIOLABO / MAIL: INFO@FUORISALONE.IT |